The Snake and the Sensei: Reflections on the History of Karate

- Jane Orton

- Nov 30, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Dec 29, 2025

Dr. Orton explores the martial art of Karate and reflects on the lessons we can learn from its history.

In his autobiography, Gichin Funakoshi (sometimes called “the father of modern Karate”) re-tells the story of how the great Okinawan Karate master Sokon Matsumura* defeated another master without striking a single blow. Matsumura had initially told a strong, well-built engraver that he was fed up with Karate, and refused to teach him, but did agree to meet him in a match.

Before a single blow was struck, Matsumura looked deeply into the eyes of the engraver, who felt a force like a bolt of lightning. The engraver collected himself, then uttered a kiai—a shout to focus power before an attack—which did not faze Matsumura. Matsumura issued his own kiai which hit the engraver like thunder. The engraver immediately submitted, saying that that he had lost whatever fighting spirit he had. Matsumura explained that the engraver was determined to win, whereas he himself was just as determined to die if he lost.

This story has become legendary in the history of Karate and is one of many fantastic tales about Matsumura. Regardless of the historical accuracy of the narrative, its combination of fighting (and not fighting), wisdom and mystery are all things that have captured our imagination.

Okinawa

Karate as we know it today is less than two hundred years old, but it is rooted in much older forms of martial arts. Under the Ryukyu Kingdom (1429 to 1879), empty-handed fighting techniques developed among the Pechin class on Okinawa, the largest of the Ryukyu islands. These techniques were known as te.

The Pechin were a feudal class of officials and warriors (similar to the Samurai of Japan). Historians and Karate practitioners Robert Dyson and Michael Cowie point out that twentieth century Japanese accounts “tended in the early part of the twentieth century to regard Okinawa te as a peasant art, not to be mentioned in the same breath as the koryu—old school—arts of the Japanese gentleman. Strictly speaking, however, it was not practised by the ordinary people of Okinawa.”

The Ryukyu Kingdom was in some ways an independent nation, but in many practical ways it was dependent on China for trade and political support. This Chinese support allowed King Sho Hashi to unify Okinawa and found the Ryukyu Kingdom and to expand the islands’ existing trade and diplomatic links with China.

In 1429, Sho Hashi forbade the carrying of weapons by all members of the Pechin class apart from his personal bodyguard (a ban that was reintroduced in 1609 when the Shimazu clan from Japan’s Satsuma province invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom and took de facto control). As a result, Okinawa’s warrior class developed empty-handed combat styles.

There was an established population of Chinese residents in Okinawa, including scholars, bureaucrats and craftsmen. This facilitated the transmission of Chinese martial arts to the Ryukyu Kingdom, particularly the “Crane” styles of Ch’uan fa (fighting techniques that English speakers now call “Kung fu”) associated with Fujian province.

Ch’uan fa itself has deep roots in Chinese history. Martial arts were practiced in the Xia and Shang dynasties (2070–1600 B.C.), refined during the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 B.C.). Although historical sources are unclear about this, tradition holds that the Indian monk Bodhidharma came to the Shaolin temple on Mount Song in China in the sixth century A.D..

In Okinawa, Pechin families were said to pass down their secret techniques from father to oldest son, so there might have been many different styles of te at that time. Three styles are known today: Shuri te, Naha te and Tomari te. As the Okinawa te was refined alongside Chinese influences, it came to be known as tode (the Okinawan name) or “karate” (“Chinese hand” or “empty hand”). Early masters include Chatan Yara (1668–1756), Takahara Pechin (1683–1760), Sakugawa Kanga (1733–1815), and Matsumura Sokon (ca 1797–1889).

The Ryukyu Islands were formally annexed by Japan in the 1870s, becoming known as the Okinawa prefecture. As a result, Karate was able to spread to mainland Japan.

Karate in the Twentieth Century

In the twentieth century, Okinawan Karate master Anko Itosu ended the secrecy surrounding Karate and began teaching to outsiders. Gichin Funakoshi, one of Itosu’s students, demonstrated Karate to the crown Prince of Japan (later to become Emperor Hirohito) whilst on a trip to Okinawa. Funakoshi was invited to Japan to teach.

Funakoshi and made modifications to the art. He helped to form the Japanese Karate Association (JKA) and advocated for Karate as a means to building character, not just self-defence.

Following the second World War, American soldiers learned Karate while living on military bases in Okinawa and this spread Karate to the rest of the world. It was now much easier to set up a dojo (Karate school) and increased immigration helped Karate to spread.

Karate Styles

Karate is a mixture of kicking techniques and hand techniques. It includes kihon (basic techniques), kata (a set sequence of movements) and kumite (sparring). Students are taught by a sensei (teacher).

There are commonalities among all styles of Karate. Practitioners wear a gi and work towards belts whose colours show their stage in their Karate education: white, yellow, orange, green, blue, purple, brown kyu belts and black dan belts. Dan belts themselves are sometimes ranked in degrees, with each higher rank often earning more stripes on the belt (although some traditionalists dislike the idea of these).

Funakoshi is credited as the founder of Shotokan Karate following his trip to Tokyo in 1921. This is a classification to which Funakoshi objects, maintaining that, “There is no place in contemporary Karate-do for different schools.” “Shoto” is actually the name Funakoshi used to sign his poems—it means “pine waves,” reflecting the murmur of wind in the pines among which Funakoshi used to find solitude. Shotokan aims to produce powerful strikes fast, so it uses wide stances and linear techniques.

Funakoshi’s reasoning for objecting to these classifications is that “all these ‘schools’ should be amalgamated into one so that Karate-do may pursue an orderly and useful progress into man’s future.” Karate teachers met in Naha City in 1936 to try to unify Karate and decide on common kata. Today, however, there are still different styles. Broadly—and this is a broad generalisation—other “schools” of Karate include:

Shito-ryu Karate, associated with Kenwa Mabuni in 1928. It has around fifty katas and emphasises powerful, precise striking. Shukokai (“Way for All)” was created in 1946 by Chojiro Tani Sensei as a branch of Shito ryu (often called Tani-ha Shito ryu). This uses a high stance for fast movement, and double hip twists for powerful strikes.

Wado-ryu (“way of harmony”) was formed by Hienori Otsuka is 1939. It is known for harmonious movement and evading attacks without excessive force. Goju-Ryu was established in 1930 by Chojun Miyagi. It uses soft, circular blocking techniques, and is influenced by Chinese forms. Goju ryu and Wado ryu can include close-quarter grappling techniques as well as striking and elements of ju jutsu.

Karate-do

Do means “way” or “way of life” and this is a common way for practitioners to think about their relationship with Karate. This can mean many different things, and Funakoshi himself offers assorted explanations of the essence of Karate-do.

One such explanation involves “winning by losing,” illustrated by the story of how his teacher Itosu forbade his students to use their skills against a gang of thugs who attacked them. Itosu then took the students on an alternative route home to avoid further trouble. This, Funakoshi suggests, is the meaning of Karate-do.

The Sensei and the Viper

Funakoshi also offers a contrasting explanation of the essence of Karate-do, involving his encounter with a habu, a venomous pit viper found in Okinawa. He came across the habu when he was out with his young son. It was coiled to strike, but after a staring contest with Funakoshi, it slithered off into a potato field. When Funakoshi looked into the field to make sure the habu had retreated, he found the viper lying in wait for him. “…when it slid off into the field it was not running away from us,” says Funakoshi. “It was preparing an attack. That habu understands very well the spirit of Karate.”

These anecdotes seem contradictory, but another way of looking at it is that they reflect the fluidity of Karate-do and a recognition of the impermanence with which we must all come to terms.

Funakoshi lost many students to the battles of the Second World War and he describes his heartbreak as he prayed for them in his dojo. Funakoshi’s dojo itself was destroyed in an air-raid in 1945—a dojo that had been “built with love and generosity by friends of Karate-do…the most wonderful thing that I had ever accomplished in my life.”

Returning to the story of Matsumura’s victory, with which we opened, Funakoshi relates Matsumura’s own reflections on this: “I’m a human being, and a human being is a vulnerable creature, who cannot possibly be perfect. After he dies, he returns to the elements—to earth, to water, to fire, to wind, to air. Matter is void. All is vanity. We are like blades of grass or trees in the forest, creations of the universe, of the spirit of the universe, and the spirit of the universe has neither life nor death. Vanity is the only obstacle to life.”

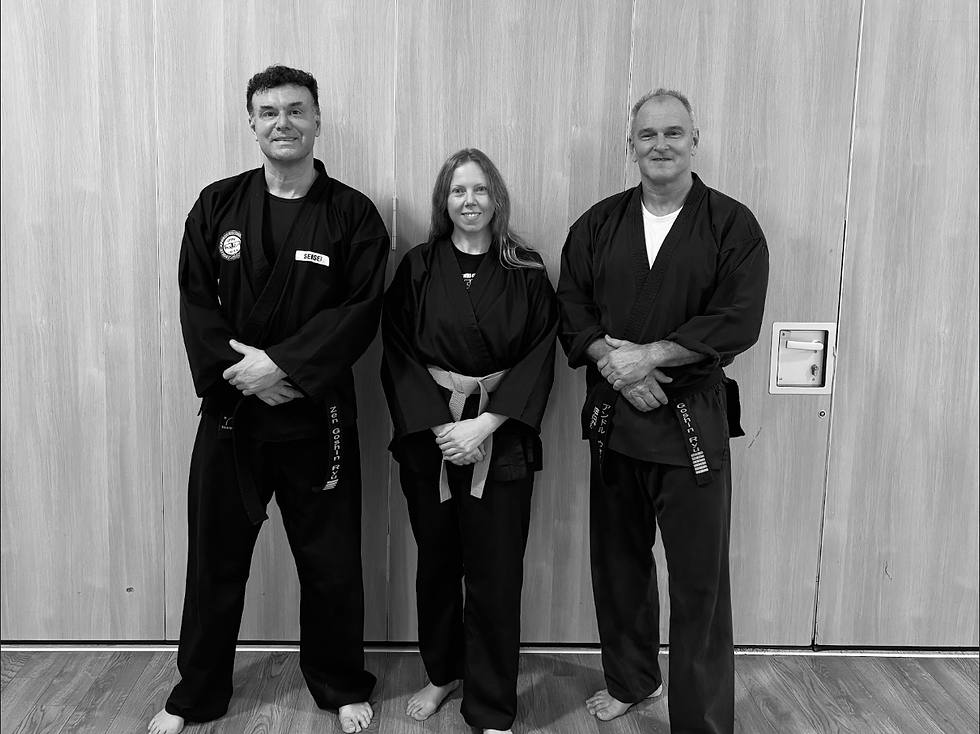

With special thanks to my friend Robert Dyson and my Karate Sensei Andy Walker of Zen Goshin Ryu Martial Arts School, for their advice and guidance.

* Japanese names usually take the form “Matsumura Sokon” (patronymic first), but I’ve used the more common English way here.

Find Out More

If you’d like to know more about the history and thought of Japan, take a look at our post on the Sacred Forest Shrines of Japan or if you’re interested in the history of martial arts, we have an interdisciplinary course on the History of Boxing! Alternatively, if you’re interested in religion and folklore, take a look at our Anthropology or Religious Studies courses.

These courses are templates of possible routes of study and can be combined, adapted, or designed from scratch to suit your interests and goals. Dr. Orton will work with you to design a course of private tutorials tailored to your needs, ability and schedule – whether you are undertaking your own research for an independent project, writing a book or simply have a personal interest. Click the link to find out what it’s like to work with her.

Contact us to find out more!

Undertake Your Own Research Project

Working on your own independent research project needn’t be a lonely task: Dr. Orton works with other independent scholars on projects in conservation and the humanities. Contact us for a chat with her.

If you’re not ready to reach out yet, follow our research methods series on this blog for more ideas! Dr. Orton has written posts on the importance of independent research and how to get started with building your own approach to ethical, people-centred fieldwork.

Reach Out

Follow our Orton Academy Instagram—we would love to connect with you!

Comments